Embarking on a cape crusade

The Australian | Saturday, July 20th, 2019

There are many magnificent twists and turns

on the scenic road to Nova Scotia.

By Cindy Fan

I set out from Baddeck at daybreak and it isn’t long before I am greeted with a vista over the sea. Hewn into the hillside, the road winds north along the eastern coast of Cape Breton Island. A crush of dark fir and rock flanks my left; the Atlantic Ocean stretches out to my right, lustrous copper at sunrise.

Separated from the rest of Nova Scotia province by a narrow strait, Cape Breton juts off Canada’s eastern seaboard like a hitchhiker’s signal. Highlands cover the raised thumb, and the thumbnail is Cape Breton Highlands National Park, a 950sq km forested plateau cut with river valleys and lakes, bound by dramatic cliffs that abruptly meet the sea.

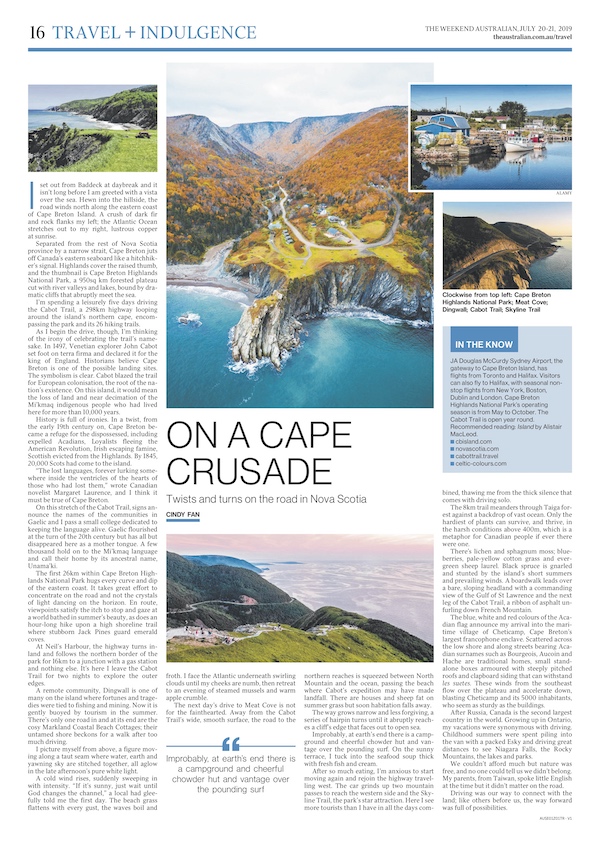

I’m spending a leisurely five days driving the Cabot Trail, a 298km highway looping around the island’s northern cape, encompassing the park and its 26 hiking trails.

As I begin the drive, though, I’m thinking of the irony of celebrating the trail’s namesake. In 1497, Venetian explorer John Cabot set foot on terra firma and declared it for the king of England. Historians believe Cape Breton is one of the possible landing sites. The symbolism is clear. Cabot blazed the trail for European colonisation, the root of the nation’s existence. On this island, it would mean the loss of land and near decimation of the Mi’kmaq indigenous people who had lived here for more than 10,000 years.

History is full of ironies. In a twist, from the early 19th century on, Cape Breton became a refuge for the dispossessed, including expelled Acadians, Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution, Irish escaping famine, Scottish evicted from the Highlands. By 1845, 20,000 Scots had come to the island.

“The lost languages, forever lurking somewhere inside the ventricles of the hearts of those who had lost them,” wrote Canadian novelist Margaret Laurence, and I think it must be true of Cape Breton.

On this stretch of the Cabot Trail, signs announce the names of the communities in Gaelic and I pass a small college dedicated to keeping the language alive. Gaelic flourished at the turn of the 20th century but has all but disappeared here as a mother tongue. A few thousand hold on to the Mi’kmaq language and call their home by its ancestral name, Unama’ki.

The first 26km within Cape Breton Highlands National Park hugs every curve and dip of the eastern coast. It takes great effort to concentrate on the road and not the crystals of light dancing on the horizon. En route, viewpoints satisfy the itch to stop and gaze at a world bathed in summer’s beauty, as does an hour-long hike upon a high shoreline trail where stubborn Jack Pines guard emerald coves.

At Neil’s Harbour, the highway turns inland and follows the northern border of the park for 16km to a junction with a gas station and nothing else. It’s here I leave the Cabot Trail for two nights to explore the outer edges.

A remote community, Dingwall is one of many on the island where fortunes and tragedies were tied to fishing and mining. Now it is gently buoyed by tourism in the summer. There’s only one road in and at its end are the cosy Markland Coastal Beach Cottages; their untamed shore beckons for a walk after too much driving.

I picture myself from above, a figure moving along a taut seam where water, earth and yawning sky are stitched together, all aglow in the late afternoon’s pure white light.

A cold wind rises, suddenly sweeping in with intensity. “If it’s sunny, just wait until God changes the channel,” a local had gleefully told me the first day. The beach grass flattens with every gust, the waves boil and froth. I face the Atlantic underneath swirling clouds until my cheeks are numb, then retreat to an evening of steamed mussels and warm apple crumble.

The next day’s drive to Meat Cove is not for the fainthearted. Away from the Cabot Trail’s wide, smooth surface, the road to the northern reaches is squeezed between North Mountain and the ocean, passing the beach where Cabot’s expedition may have made landfall. There are houses and sheep fat on summer grass but soon habitation falls away.

The way grows narrow and less forgiving, a series of hairpin turns until it abruptly reaches a cliff’s edge that faces out to open sea.

Improbably, at earth’s end there is a campground and cheerful chowder hut and vantage over the pounding surf. On the sunny terrace, I tuck into the seafood soup thick with fresh fish and cream.

After so much eating, I’m anxious to start moving again and rejoin the highway travelling west. The car grinds up two mountain passes to reach the western side and the Skyline Trail, the park’s star attraction. Here I see more tourists than I have in all the days combined, thawing me from the thick silence that comes with driving solo.

The 8km trail meanders through Taiga forest against a backdrop of vast ocean. Only the hardiest of plants can survive, and thrive, in the harsh conditions above 400m, which is a metaphor for Canadian people if ever there were one.

There’s lichen and sphagnum moss; blueberries, pale-yellow cotton grass and evergreen sheep laurel. Black spruce is gnarled and stunted by the island’s short summers and prevailing winds. A boardwalk leads over a bare, sloping headland with a commanding view of the Gulf of St Lawrence and the next leg of the Cabot Trail, a ribbon of asphalt unfurling down French Mountain.

The blue, white and red colours of the Acadian flag announce my arrival into the maritime village of Cheticamp, Cape Breton’s largest francophone enclave. Scattered across the low shore and along streets bearing Acadian surnames such as Bourgeois, Aucoin and Hache are traditional homes, small stand-alone boxes armoured with steeply pitched roofs and clapboard siding that can withstand les suetes. These winds from the southeast flow over the plateau and accelerate down, blasting Cheticamp and its 5000 inhabitants, who seem as sturdy as the buildings.

After Russia, Canada is the second largest country in the world. Growing up in Ontario, my vacations were synonymous with driving. Childhood summers were spent piling into the van with a packed Esky and driving great distances to see Niagara Falls, the Rocky Mountains, the lakes and parks.

We couldn’t afford much but nature was free, and no one could tell us we didn’t belong. My parents, from Taiwan, spoke little English at the time but it didn’t matter on the road.

Driving was our way to connect with the land; like others before us, the way forward was full of possibilities.

In the Know

JA Douglas McCurdy Sydney Airport, the gateway to Cape Breton Island, has flights from Toronto and Halifax. Visitors can also fly to Halifax, with seasonal non-stop flights from New York, Boston, Dublin and London. Cape Breton Highlands National Park’s operating season is from May to October. The Cabot Trail is open year round. Recommended reading: Island by Alistair MacLeod.

This feature was published in The Weekend Australian – Destination Canada special on July 20, 2019.