Into the melting pot

The Australian | Saturday, April 13th, 2019

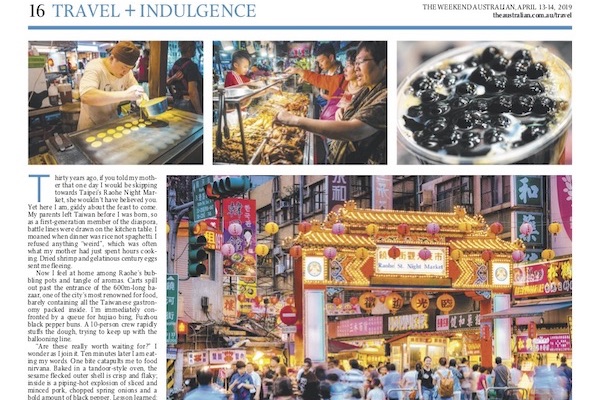

Take a feast down memory lane at Taipei’s famous Raohe Night Market.

By Cindy Fan

Thirty years ago, if you told my mother that one day I would be skipping towards Taipei’s Raohe Night Market, she wouldn’t have believed you. Yet here I am, giddy about the feast to come. My parents left Taiwan before I was born, so as a first-generation member of the diaspora, battle lines were drawn on the kitchen table. I moaned when dinner was rice not spaghetti. I refused anything “weird”, which was often what my mother had just spent hours cooking. Dried shrimp and gelatinous century eggs sent me fleeing.

Now I feel at home among Raohe’s bubbling pots and tangle of aromas. Carts spill out past the entrance of the 600m-long bazaar, one of the city’s most renowned for food, barely containing all the Taiwanese gastronomy packed inside. I’m immediately confronted by a queue for hujiao bing, Fuzhou black pepper buns. A 10-person crew rapidly stuffs the dough, trying to keep up with the ballooning line.

“Are these really worth waiting for?” I wonder as I join it. Ten minutes later I am eating my words. One bite catapults me to food nirvana. Baked in a tandoor-style oven, the sesame flecked outer shell is crisp and flaky; inside is a piping-hot explosion of sliced and minced pork, chopped spring onions and a bold amount of black pepper. Lesson learned: when in doubt, follow the crowd.

Raohe isn’t so much a night market as a university dedicated to xiaochi (“little eats”). These hearty snacks teach the story of Taiwan’s history over the past few centuries, the waves of immigration from different regions of China, including my own Hakka ancestors, as well as a string of colonial rulers, most notably Japan from 1895 to 1945.

Xiaochi is elemental to the island’s culture: we eat a little a lot, and at all hours. Night-market vendors dedicate their lives to making each delicacy. Like tapas, one dish is not a full meal and it’s eaten knowing there will be room for something else. It’s a slippery slope for gluttons like me.

A heady, herbal scent redolent of my childhood lures me to my next something else, medicinal pork rib soup. Medicinal soups were a staple in my home. There was always something bubbling on the stove that was supposed to be good for me. I quickly learned there were two types: ones that were delicious and others that tasted like poison. Obviously this is the delicious variety, the bones infusing gentle sweetness, the herbs earthy and soothing.

I goggle at stall after stall. Braised beef shank, cowheel and honeycomb tripe simmer with spices. A vendor uncovers a wooden box releasing a plume of steam; pig blood curd warms inside. A pancake of starchy batter, oysters and egg sizzles on a hot plate before it’s smothered in sweet-chilli sauce; oyster omelette o-a-chian is a staple at any night market. So is savoury spring onion pancake, scrumptious plain or rolled up with beef and hoisin sauce.

There are skewers of electric-red Chinese hawthorn, a resiny candy coating offsetting the tart fruit; char siu barbecue pork spring rolls made to order; cubes of steak seared with a blowtorch; sticky rice cooked in bamboo; and mountain boar sausage, a nod to Taiwanese indigenous cuisine.

How do you want your squid: grilled, deep-fried, flash-boiled with basil? Dumplings come in the form of potstickers, soup dumplings, wontons or buns, steamed, boiled or crisped in a pan. There are balls galore — octopus, fish, taro, quail egg, sweet potato — and chicken every way imaginable, including deep-fried schnitzel larger than my face. Students flock to the buffet laden with braised chicken and duck parts such as feet, gizzards, wings, tongue, and load up plates to be tossed with seasoning.

I smell chou doufu long before I see it. Does someone have rotting gym socks? Then I’m smacked with the full pungent punch of stinky tofu. Fermentation in brine is what gives the tofu its funk, joining kimchi and fish sauce in the “malodorous and misunderstood” club. Like all fermented greats, the flavour is milder than the smell and is an acquired taste. The golden rule of snack food applies: it’s best deep-fried. Let the crispy cubes soak up a touch of soy and chilli sauce. Munch on the crunchy pickled cabbage as a palate cleanser. Stinky tofu can also be served in a fiery Sichuan soup or with duck blood curd.

The fruit-shake stands make Carmen Miranda’s hat seem dull. Here you can samba with kumquat, lychee, atemoya and more. Some self-prescribe a dose of bitter melon, a knobbly white gourd. It’s so bitter that when I first tried it as a child I burst into tears. It’s supposed to be good for you (I can hear my mother’s voice again), especially for digestion. Keep that in mind after garlicky, fatty, sugary Taiwanese sausage, a guilty pleasure.

Don’t forget the shops that line Raohe offering fare that requires a sturdy table. In between foot massages and fortune tellers who divine futures through sticks, cards or faces, there are hot pots and hot plates, steaks served still furiously spitting. The bolthole at 94 Raohe Street has been making Taiwanese noodle favourite oamisoir since the 1930s. Its version is more delicate than the normally claggy soup of brown vermicelli noodles, baby oysters and bits of pig intestine.

But my love letter would be to beef noodle soup, a gastronomic wonder. Brought by Kuo-mintang veterans who fled Sichuan during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s, like so many of Taiwan’s dishes, it evolved and became the country’s own. Fresh, sturdy noodles swim in a dark, umami-rich broth that hints at star anise and spicy bean paste, and sings with the tough cuts of beef slow cooked to near collapse. With one slurp I am simultaneously homesick and caught in a deluge that sweeps me home.

Dessert is a crash course in Taiwan’s obsession with an untranslatable bouncy, slippery, rubbery texture known as “Q”, or “QQ” to emphasise the springiness. Take boba for example, otherwise known as bubble tea, a drink loaded with tapioca pearls, jellies, sweetened beans and fruit. QQ fare is also heaped on to shaved ice, a remedy to the island’s humid summer nights. It’s impossible to walk a few metres in Raohe without coming across mashu (“mochi” in Japan), sticky viscoelastic rice cakes dredged in powdered sugar, ground peanut or sesame, or tangyuan, QQ glutinous rice balls floating in syrup.

Suspend all notions of what belongs in desserts: soft tofu in ginger syrup; red bean soup; deep-fried milk cubes. I’m intrigued by a woman scraping a slab of peanut brittle. She heaps the dust on to a thin crepe, adds two scoops of peanut ice cream — and coriander. I picture six-year-old me howling with disgust as I take a bite. It’s delightful.

IN THE KNOW

Raohe Night Market is open daily from 5pm to midnight. Songshan is the closest MRT station.

This story was published in The Weekend Australian on April 13-14, 2019.