Spice of Life

The Australian | Saturday, March 2nd, 2024

Get a taste of the West Indies on a new ocean yacht

Twelve years of studying French at school has prepared me for this moment, eavesdropping on locals in a beachfront cafe. As I gaze at the dazzling water lapping Martinique’s volcanic black sand, two dapper gents cradle their Sunday beers and wonder aloud about the sleek white vessel anchored offshore. It’s too small to be a cruise ship, and those usually dock at the capital, Fort de France. What’s it doing in sleepy Saint-Pierre and who is aboard? Well, I am, for a start, and here’s my cue to share what I know.

“That’s Emerald Sakara,” I chime in with my rusty French. Sipping a Ti’ Punch, Martinique’s national cocktail (rum served neat with wedges of lime), emboldens me to answer their questions. I announce it’s 110m long, has 50 double cabins, a pool, spa and gym, and is set to sail the eastern Caribbean for eight days.

As I chat with locals, buy passionfruit from an old woman who tries to upsell me on sarsaparilla root (“it’s good for the liver”), there’s a pervasive sense of place. Martinique is an overseas territory of France and its inhabitants are French citizens. I try to wrap my head around the fact that I am in the European Union, using Euro and walking along Rue Victor Hugo.

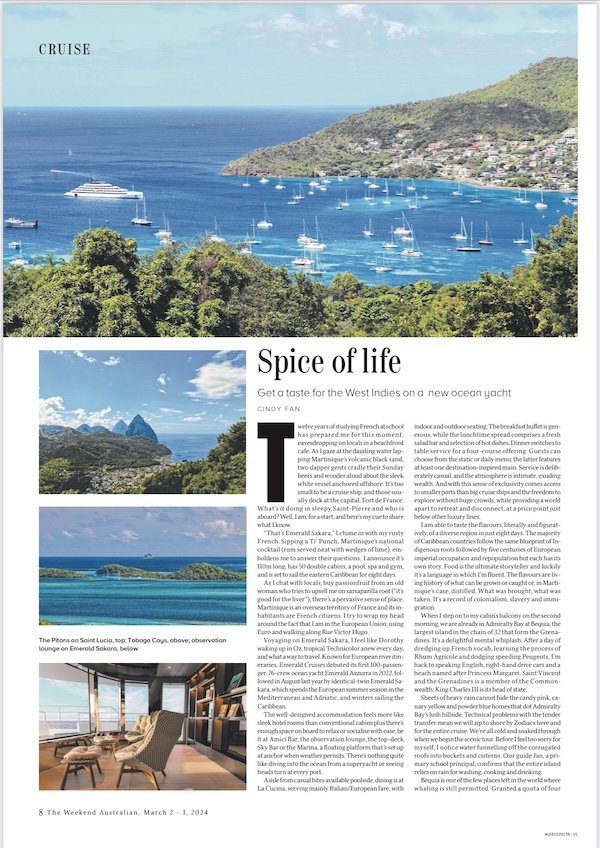

Voyaging on Emerald Sakara, I feel like Dorothy waking up in Oz, tropical Technicolor anew every day, and what a way to travel. Known for European river itineraries, Emerald Cruises debuted its first 100-passenger, 76-crew ocean yacht Emerald Azzurra in 2022, followed in August last year by identical-twin Emerald Sakara, which spends the European summer season in the Mediterranean and Adriatic, and winters sailing the Caribbean.

The well-designed accommodation feels more like sleek hotel rooms than conventional cabins plus there’s enough space on board to relax or socialise with ease, be it at Amici Bar, the observation lounge, the top-deck Sky Bar or the Marina, a floating platform that’s set up at anchor when weather permits. There’s nothing quite like diving into the ocean from a superyacht or seeing heads turn at every port.

Aside from casual bites available poolside, dining is at La Cucina, serving mainly Italian/European fare, with indoor and outdoor seating. The breakfast buffet is generous, while the lunchtime spread comprises a fresh salad bar and selection of hot dishes. Dinner switches to table service for a four-course offering. Guests can choose from the static or daily menu; the latter features at least one destination-inspired main. Service is deliberately casual, and the atmosphere is intimate, exuding wealth. And with this sense of exclusivity comes access to smaller ports than big cruise ships and the freedom to explore without huge crowds, while providing a world apart to retreat and disconnect, at a price point just below other luxury lines.

I am able to taste the flavours, literally and figuratively, of a diverse region in just eight days. The majority of Caribbean countries follow the same blueprint of Indigenous roots followed by five centuries of European imperial occupation and repopulation but each has its own story. Food is the ultimate storyteller and luckily it’s a language in which I’m fluent. The flavours are living history of what can be grown or caught or, in Martinique’s case, distilled. What was brought, what was taken. It’s a record of colonialism, slavery and immigration.

When I step on to my cabin’s balcony on the second morning, we are already in Admiralty Bay at Bequia, the largest island in the chain of 32 that form the Grenadines. It’s a delightful mental whiplash. After a day of dredging up French vocab, learning the process of Rhum Agricole and dodging speeding Peugeots, I’m back to speaking English, right-hand drive cars and a beach named after Princess Margaret. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a member of the Common- wealth; King Charles III is its head of state.

Sheets of heavy rain cannot hide the candy pink, canary yellow and powder blue homes that dot Admiralty Bay’s lush hillside. Technical problems with the tender transfer mean we will zip to shore by Zodiacs here and for the entire cruise. We’re all cold and soaked through when we begin the scenic tour. Before I feel too sorry for myself, I notice water funnelling off the corrugated roofs into buckets and cisterns. Our guide Jan, a primary school principal, confirms that the entire island relies on rain for washing, cooking and drinking.

Bequia is one of the few places left in the world where whaling is still permitted. Granted a quota of four humpbacks a year, the average has been one per year since 1986; in comparison, Iceland, Norway and Japan combined have killed more than 1000 whales annually in the past decade. Jan’s vibrant manner becomes tentative as she shares details of the entrenched tradition and what it means to the community; I sense she’s endured condemnation from visitors. Every part of the whale is used, she explains. The salted, dried meat ensures families have protein for months, clearly important for an island solely dependent on tourism and fishing.

I take advantage of Sakara’s late departure to take a shuttle back into Bequia for an early dinner ashore. The port is eerily quiet at 5pm. Seabourn and Silversea ships are already sailing away. At welcoming Laura’s Restaurant, with 10 tables by the water’s edge, I order callaloo, a soupy stew of okra and taro greens, vegetables that were brought by enslaved people from Africa. “We call it a blood soup,” the waitress proclaims as she emphasises its health benefits. Callaloo varies across the Caribbean, sometimes with crab or meat or, like this restaurant’s version, simply vegetarian.

The next two days on the cruise itinerary showcase Emerald Sakara’s nimble size. At Tobago Cays, an archipelago of five deserted islets within a marine reserve, we anchor amid posh private pleasure crafts for the quintessential Caribbean fantasy of brilliant blue water, powdery white sand, snorkelling with sea turtles and rays and, yay, fresh seafood.

Competing proprietors Alphonso and Captain Kojak flaunt big spiny lobsters we can reserve for lunch, grilled with butter, and served alongside frosty Hairoun beer, brewed in St Vincent.

On Mayreau, population 250, our day at the beach includes a barbecue and use of kayaks, SUPs and Seabobs, handheld scooters that zip up to 20km/h. I’m grateful for the generous spread hauled over by the crew but I am puzzled. There are hamburgers, steak, ribs, fish and bland chicken, heaps of potato and pasta side dishes, but a glaring lack of anything local. Why not make just one of the meats jerk-style? This spicy marinade, which originated in Jamaica, is now popular throughout the West Indies. Or have roasted breadfruit or banana fritters, two staples of St Vincent and the Grenadines?

Breadfruit and bananas abound on fertile Saint Lucia, along with coconuts and mangoes. These fruits were brought to the Caribbean in “the Columbian exchange”, the transfer of plants, animals and, yes, diseases from Eurasia and Africa following Columbus’s 1492 voyage.

After tourism, agriculture is Saint Lucia’s most important economy, with bananas accounting for 96 per cent of the total export. Criollo, one of the finest, rarest cacao varieties, is also grown here. Instead of docking alongside cruise ships at Castries, the capital, we anchor at Soufriere on the southwest coast of the mountainous, teardrop-shaped island where the iconic dual volcanic spires, the Pitons, dramatically flank the bay. Our hike to a panoramic viewpoint is rewarded with accra, fried salted cod fishcakes dipped in “banana ketchup”, a zingy yellow alternative to standard tomato sauce.

At Fedo’s in Soufriere, the Vite family has been dish- ing up favourites such as shrimp Creole for 31 years. I sip hibiscus iced tea infused with island-grown cinnamon, cloves, star anise and ginger, and feast on chicken roti. After the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies, the British brought 4000 indentured labourers from India to work Saint Lucia’s sugarcane plantations. Indian dishes such as roti were adapted with available ingredients and are now part of Saint Lucian cuisine.

Having sampled the many flavours of the region on this sailing, it’s time for dessert. Terre-de-Haut is a dreamy 3.5sq km isle that’s part of the Les Saintes archipelago in Guadeloupe. Palms, fishing dinghies and bistros line the water, along with traditional Creole huts, and colourful squat wooden buildings with jalousie doors.

At a tiny bar by the pier, I savour mouthfuls of le tourment d’amour, the agony of love. Bless the French for such a romantic name. It’s a tart filled with cinnamon- spiced genoise sponge and coconut jam. The story goes that sailors’ wives made these as they anxiously waited for the return of their men. If this is what agony feels like, then I want more.

Cindy Fan was a guest of Emerald Cruises.

IN THE KNOW

Emerald Cruises offers Caribbean itineraries inclusive of all meals, drinks, gratuities and selected excursions. Its next Caribbean season runs from December 2024, featuring 15-day itineraries between Bridgetown, Barbados, and Marigot, Saint Martin. From $9049 a person, twin-share. emeraldcruises.com

This Emerald Sakara review: cruising the Caribbean was published in The Weekend Australian’s Travel+Luxury March 2-3, 2024